I’m certainly not well versed in Art; I know what I like, but I can seldom explain why, or even name the artist, let alone their style. Also, I would usually be just as pleased to have a poster reproduction of some famous work of art on my wall as I would the framed original in its oils or watercolours. I suppose I’m reacting to the effect it has on me, rather than anything else.

Some Art -or should I say some artists- occasionally capture something that is difficult to describe, difficult to name, but which draws me into it nonetheless. Sometimes it is as simple as their treatment of the subject matter -Van Gogh comes to mind, or perhaps J.M.W. Turner and his use of light and often rather imaginative depictions of his marine subject matter; sometimes it is the effect of the message being conveyed, such as Edvard Munch’s The Scream, or the fanciful sketch by Pablo Picasso of Don Quixote sitting on his horse with his side-kick Sancho Panza in the background…

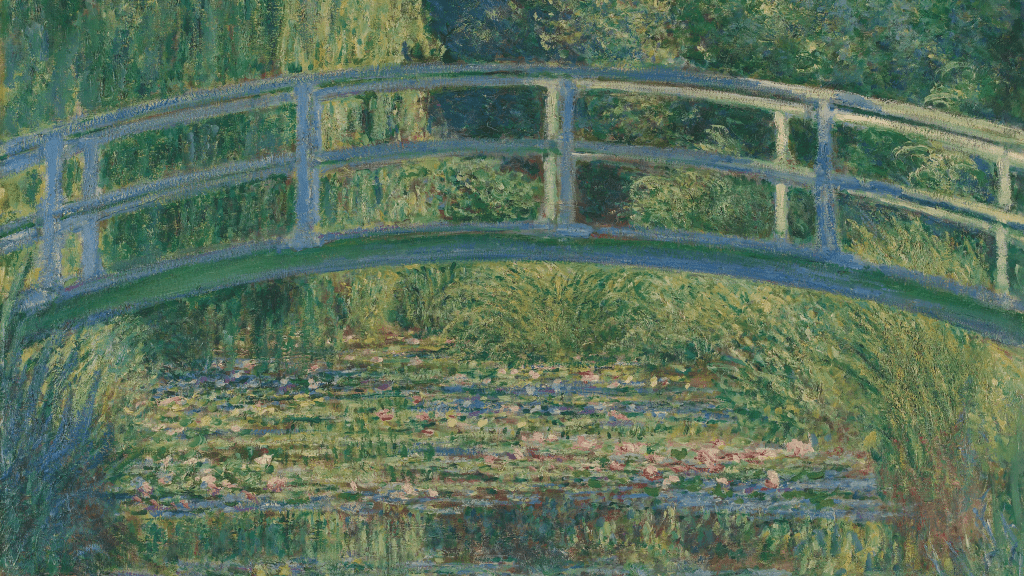

Those works, and many others of course, have drawn me in over the years, but I have seldom tried to understand why. The many paintings of Claude Monet’s water lilies though have continued to puzzle me. On first glance -or maybe second and third, if I’m honest about it- they all seem the same: just multiple colours and shadows of things floating in a pond in a leafy garden somewhere, but entrancing nonetheless. Nothing is happening -no drama is unfolding, no message is being whispered about the why of the seemingly endless depiction of water lilies, except perhaps the magic that after so many years I am still wondering about them.

Often, if I don’t stop to analyse it, I relax and find I am immersed in… well, in something. It’s not the vast territory of a landscape; its more the closeness of chancing upon a small, hidden pond in a forest somewhere, I suppose -a relaxing, peaceful, unexpected find. I am there as an unwitting guest in a secret garden. And, being there, I am no longer conscious of its size, just of being a part of it, without the need to question its existence. I am not an interloper, but a part of it, somehow -I am in a place where I am meant to be and not question its existence… or mine.

For some reason, Monet’s pond reminds me of happening upon the magical town Brigadoon, a mysterious Scottish village which appears for only one day every 100 years, and made famous by the Lerner and Loewe musical of the same name. To see it, to experience it, is serendipitous; to feel it beckoning to me is irresistible, and yet despite the invitation for me to approach more closely I still suspect I might be trespassing…

There is an ‘atmosphere’ to the pond, a mood that prolonged inspection offers, although I’m not really sure that I can explain it in more detail. I have to thank an article about Monet’s water lilies for the reason I am questioning it at all.[i] Among other things, the author writes that ‘Monet was foreshadowing advances in philosophy that have only recently made it into mainstream discourse. There has been a renewed focus on atmospheres in phenomenology, and this trend has now permeated into geography, anthropology and architecture… atmospheres are phenomena that characterise spaces (real or imaginary) and are grasped prior to any reflection, through our bodies and our feelings.

‘Atmospheres are ephemeral. And yet, it is a recurring notion that atmospheres are somehow the heart of the place, something that Monet hints at when he says that landscapes come to life only through their atmospheres… This is a radical idea. If anything, most people, when thinking about how they experience a scene, would follow an atomist view: there are small elements that join together to make bigger elements, and bigger elements (a table) combine into even bigger ones (a dining room). And then the atmosphere comes last. The atmosphere of The Water-Lily Pond, for example, would be made out of the bridge, the pond, the trees. But Monet says that it’s the other way around: the bridge, the pond and the trees emerge thanks to the atmosphere.’

If you think about it, ‘atmosphere’ is happening all the time for us as we travel through our day. For example, the worry which may suddenly envelope us as we approach the cash register in a store as to whether we really need the items we are about to purchase. Walking from the darkness of a movie theatre into the full sunshine of a summer afternoon can quickly change our feeling about the day; entering a quaint little store through a door with tiny bells tinkling over it as it opens; the smell of a used bookstore, or the laughter of some little children in a playground can all change our mood. Nothing is static; our days are journeys through different moods. ‘It seems that extracting the gist of a scene (the Gestalt) is often the priority for the perceptual system.’

And as the author puts it in yet another way, ‘As you move from one building to another, from a garden to the street, notice how the changes in light, the opening and closing of vistas, affect your mood, subtly altering your very sense of being. They are hard to notice and easy to forget, but much of what you perceive, of what you think, of what appears possible, is determined by atmospheres.’

Monet’s water lilies do not require an explanation, really; they just create a feeling. There is no doubt what a sunset means to me: it does not require someone to point it out. For that matter, does Love really require a clarification? Is it not also an atmosphere? A gestalt? Surely it is the feeling that defines it. As Hamlet says of his love for Ophelia in Shakespeare’s play: ‘Doubt thou the stars are fire; Doubt that the sun doth move; Doubt truth to be a liar; But never doubt I love.’

Isn’t that also why some Art is… special?

[i] https://psyche.co/ideas/monet-understood-the-elusive-power-of-a-places-atmosphere?

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- April 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

Leave a comment